A website devoted to teaching/playing/composing for/ the King of Instruments

May. 26, 2016

Open Score, Part II

(con't from Part I)

Those dreaded C clefs !!

Reading music in the C clefs, like reading the treble (G) clef and bass (F) clef, is a matter of familiarity; the symbol for the C clef has 2 semicircles that curve into the middle of the staff and basically "point" toward the line which identifies the note C4 (middle C on the piano).

Since this is a movable clef, we can place it anywhere we want on the staff, and whatever line it's 2 semicircles point to becomes middle C.

As long as we know that this clef always points to the line that represents middle C, we then know how to decipher the notes on the staff marked with this clef.

Since in the Western music system of notation middle C is always marked on a line, there are thus 5 possible positions for the C clef, the most common being with the pointer on the 3rd (center) line, where it's known as the alto clef (photo; orchestral and chamber music parts for viola are commonly written in this clef.

When the C clef pointer is on the 4th line up it's known as the tenor clef (photo); orchestral parts for trombone are sometimes notated in this clef.

When the C clef pointer is on the first (bottom) line we have the soprano clef; when it's on the second line, it's the mezzo-soprano clef, and when it's on the 5th (top) line it's the baritone clef.

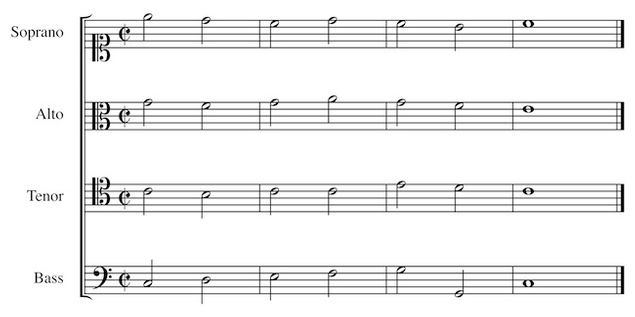

If we're looking at 4-part (SATB) Open Score (photo), figuring out the notes on the various lines and spaces when reading these C clefs the alto and tenor clefs shows us middle C, and we fill in the blanks.

For the alto clef, we simply shift the mnemonic "Every Good Boy Does Fine" down a step from its original position on the treble clef and we have the E starting in the space from below the staff; the F in the mnemonic "F-A-C-E" is then shifted down a step to the first line.

Here it helps to think of the note name in treble clef and "read" this one line or space higher ... "read up, recognize down."

For the tenor clef, we simply shift Every Good Boy Does Fine up a step from its original position on the treble clef, and we have the E starting from the first space on the bottom; the F in F-A-C-E is then shifted up a step to the second line.

Here it helps to think of the note name in treble clef and "read" this one line or space lower ... "read down, recognize down."

If we look at the phrases and words connected to other clefs there is this same basic pattern: E-G-B-D-(F)-A-C-E.

Starting with Every Good Boys Does Fine and then adding F-A-C-E a step above the E will work on all staffs in one form or other.

For example, the F (bass) clef mnemonic "Good Boys Do Fine Always" is simply the Every Good Boy phrase with the E and an added A at the top, and corresponds to the same pattern.

For the soprano clef therefore, we shift Every Good Boy Does Fine up 2 steps from its original position on the treble clef, so that we have E starting on the second line; the F in F-A-C-E is then shifted up 2 steps to the second space.

If we have an opportunity to practice music like this in advance, there are a few things we can do:

Practicing systematically is probably the most common piece of advice we'll receive; careful, systematic practice is a helpful first step toward developing this skill and training our brain to read 4 lines of music at once.

We begin by playing each part individually, then soprano and alto parts with our right hand, then tenor and bass parts with the left hand.

Once we've done this, we then practice them in all 2 part combinations (SA, ST, SB, AT, AB, TB), again, trying to keep SA parts in our right hand and TB parts in our left.

Once we're comfortable with 2 part combinations, we then try playing 3 parts (SAT, SAB, STB, ATB); we look for patterns that are the same across parts, or places where parts move together in thirds, sixths, etc.; after rehearsing all 3 part combinations, we move to reading all 4 parts in a slow, steady tempo.

Writing in the chord symbols is a trick that seems to work great for chorales and more homophonic choral works (where all the voices move together or have similar rhythm); the chord symbols (e.g. C, D7, G, Am) can be written above the staff to mark places where the harmony changes.

If we have the time, and if the parts are fairly complex (e.g., a fugue), it might be a good option to make our own piano reduction; we can use our favorite notation software to create a new score.

As with most things, the best way to improve our open score reading skills is by practicing; the more we do it, the easier it will become.

In preparing for the FAGO examination it may be most helpful to work with each clef separately, then combine them.

In this regard the book "Preparatory Exercises In Score Reading" by Howard Ferguson, published by Oxford University Press, can be a big help.

The transcribing of hymns into C clefs, open score, can also be helpful.

The Dover edition of "J.S. Bach: Eleven Great Cantatas" contains ample material including a number of open score chorales.

These do not yield easily, and it can be a peculiar mental agony to reconfigure such a thing as clef space, but the reward will be great.

The AGO exams [See blog, American Guild of Organists (AGO)] do not replicate academic programs but uphold elements of classic training that every organist is well advised to preserve; they will challenge people but also pay rich dividends.

Don't let it terrozie you -- wade into it a staff at a time.

You may feel like you're in hell for a few weeks, but it yields a skill that will open more doors for you.

Share this page