A website devoted to teaching/playing/composing for/ the King of Instruments

Nov. 22, 2019

Break It Down

Let's say that an important event is approaching at year's end at which we will be expected to perform twenty holiday songs that we don't know, it's all new music, we've been given only two weeks notice, we're already up to our ears in learning other new music, and there just doesn't appear to be enough hours on the clock to work up good arrangements of everything in time.

Or again, let's say our teacher has assigned some new "work horse" piece from the repertoire that we don't know, it's a major work that we're expected to bring to our next lesson, we're already working on five new big pieces, and there just doesn't seem to be enough time for us to get this extra assignment under our fingers and feet before then.

Given this kind of time frame, a task like this can seem beyond the realm of possibility and flat out overwhelming.

It can even throw some of us into a mild panic.

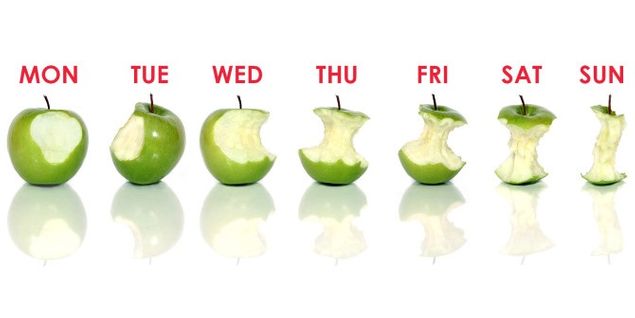

If we try to learn all of it at once our limited practice time will seem grossly insufficient, but if we break that big assignment down into smaller chunks and narrow our learning down to just a couple of these smaller bites a day and learn them well -- every day for two weeks -- at the end of that time we're much more likely to see results.

Whenever a task seems more than what we have time to take on, we find it counterproductive to tackle the entire thing from the get-go.

The strategy that makes the most efficient use of time is to divide a huge task into smaller ones, spread these chunks evenly across the available time span, and then concentrate our effort on one or two of these chunks each day.

Whether it's learning a new piece, a new group of pieces, composing a new piece of music, or digesting our way through any new reading material, the entire foundation of the educational system of Western civilization from pre-school to college is founded upon breaking things down like this into more diminutive tasks upon which the learner's attention can be centered in regular sequence.

This approach to management of time may seem a little old-fashioned in this free-wheeling society in which we live, but there are a lot worse things that can happen to someone's thinking than for it to end up being a little old-fashioned, especially with respect to learning.

Anything old-fashioned is old because it's been around a long time -- long enough for it to have been battle-tested time and time again and relied upon to produce consistent results by more than one generation.

Old-fashioned ideas are old because they work.

Share this page